As the world observes World Cancer Day on 4 February, one intrinsic factor shapes how the deadly malady is treated in South Asia—caste.

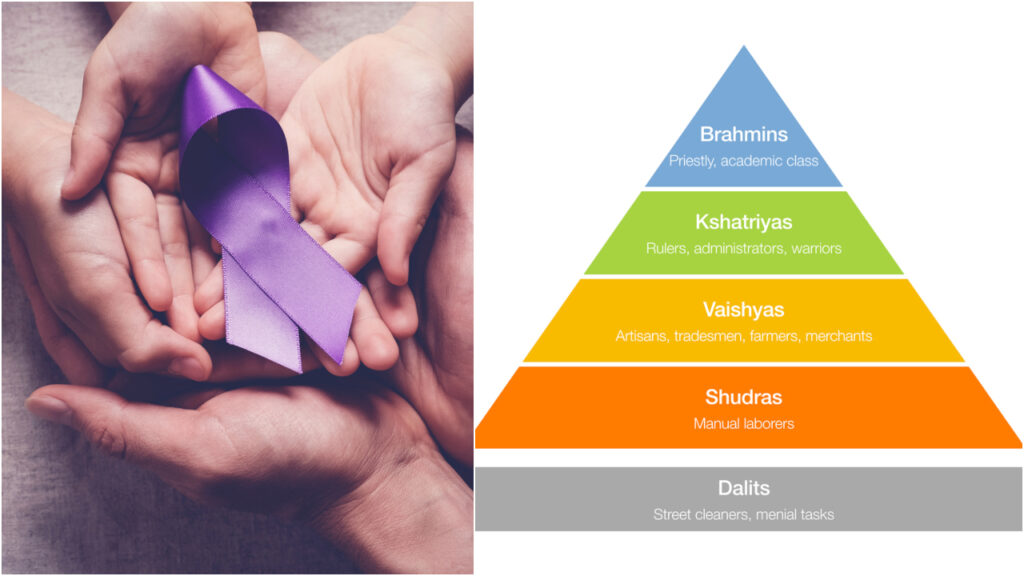

Caste creates invisible barriers that operates long before a patient even reaches the hospital. Despite legal abolitions and affirmative action policies, the ancient Indian hierarchy system persists in shaping access to screening, diagnosis, and treatment for millions.

A major new analysis published in The Lancet Global Health warns that cancer outcomes across the region are shaped not just by poverty or weak health systems, but by “the overlapping effects of caste, gender, religion, language, geography, and social exclusion, creating layered barriers that leave millions without timely diagnosis or treatment,” said the authors.

The analysis was authored by a multidisciplinary group of clinician-researchers and public health experts based in leading cancer and academic institutions across India, North America, and South Asia. The authors are affiliated with institutions including Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine in the United States, MOSC Medical College in Kerala, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, Queen’s University in Canada, and Tata Memorial Hospital and the National Cancer Grid in Mumbai.

The team includes medical doctors, radiation oncologists, surgeons, and epidemiologists with expertise in oncology, global health, and cancer policy, lending clinical and research depth to the findings.

India: Where discrimination follows patients into clinics

“Caste and ethnic identity are major determinants of access to health care in SAARC countries, resulting in substantial disparities in cancer diagnosis and treatment,” the researchers state.

In India, marginalised populations such as Dalits—historically referred to as “untouchables”—”face systemic barriers due to sociopolitical discrimination and the legacy of the caste system.”

Despite the legal abolition of caste-based discrimination, “the effects of this hierarchy persist,” said the authors. In India, “Dalits have some of the worst health outcomes,” according to the study. Whilst “affirmative action policies have been implemented to reduce these disparities in public services,” their “effect on health care remains minimal due to poor implementation and use,” the researchers found.

The researchers explain that “discrimination against low-caste communities contributes to their poor socioeconomic status, limits their access to health-care services, and perpetuates intergenerational poor health.”

The data reveals a troubling paradox. Whilst “participation in India’s health insurance programme, Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana, is higher among scheduled tribe households (18·9 percent) and scheduled caste households (14·1 percent) than among high-caste groups (9·3 percent),” the study notes that “this reliance on government schemes does not fully address the substantial barriers that these groups face in receiving adequate cancer care,” said the authors.

For Dalit women, the barriers multiply through what researchers call “double discrimination.” The study reports that “74·4 percent of Dalit women in India reported difficulties in accessing health care, and only 54·6 percent received professional antenatal care, compared with 70·3 percent of upper-caste women.”

These gaps have direct implications for cancer screening, as the researchers note that “Dalit women face double discrimination due to their caste and gender, further limiting their ability to receive timely cancer care and screenings,” said the authors.

‘Invisible’ patients of Nepal

Nepal presents perhaps the starkest evidence of how caste shapes cancer outcomes. The analysis reveals that “Dalits who make up between 13·6 percent and 20 percent of Nepal’s population, yet accounted for only 4·8 percent of cancer diagnoses.”

By contrast, the study found that “Brahmin and Chhetri castes had the highest proportion of cancers diagnoses (30·8 percent), followed by Newar (22·7 percent), Janajati (19·7 percent), and Terai caste (16 percent).”

This dramatic under-representation, the researchers suggest, is “potentially due to selective coverage of the population-based cancer registry, under-reporting, and inadequate access to health-care services,” the authors noted. The numbers suggest that large numbers of Dalit cancer patients never enter the health system at all—remaining invisible, suffering and dying without diagnosis or treatment.

The study emphasises that “caste-based discrimination intersects with geographical isolation and poverty, severely restricting health-care access for Dalit and indigenous women and children,” said the authors.

Research on healthcare use in Nepal showed that “children from marginalised communities, such as Dalit and Madhesi groups, face substantial barriers in accessing health care due to caste-based discrimination and remoteness of health-care facilities.”

Pakistan: Unacknowledged hierarchy

Even where caste systems are less openly acknowledged, they continue to shape health outcomes. The researchers note that “in countries such as Pakistan, where the caste-like system (zaat or qaum) is less openly acknowledged, it still plays a substantial role in perpetuating health-care inequities,” said the authors.

A study cited in the research “revealed that 49·5 percent of respondents identified as low-caste groups, including Kammi and its sub-castes, and these groups faced greater barriers in accessing essential health services than high-caste groups.”

The disparities begin at birth. The study found that “34·5 percent of low-caste women said they had unskilled attendants during childbirth, compared with 16·1 percent in high-caste groups.” These inequities in maternal care, the researchers argue, have “implications for early cancer detection and treatment,” said the authors.

An ethnographic study on maternal deaths in Pakistan, referenced in the analysis, “highlighted how caste and poverty intersect to prevent lower-caste women from accessing life-saving maternal health care, even when services are physically available.”

Bangladesh: Ethnic minorities left behind

In Bangladesh, “ethnic minorities, such as the Rohingya and tribal communities in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, face severe barriers to health care.” For the Rohingya, “over 1 million displaced people live in camps in Cox’s Bazar,” where “cancer care is almost non-existent.”

The study notes that “Rohingya refugees face multiple layers of exclusion due to their displaced refugee status, ethnicity, poverty, and compromised social identity,” and “these combined factors prevent this population from accessing cancer care and other key health services,” said the authors.

Tribal groups “such as the Chakma and Marma, are affected by health-care inequities due to geographical isolation.” The research explains that “these communities often rely on traditional healers, such as the Badi, and delay formal medical care,” whilst “years of conflict and underdevelopment in the Chittagong Hill Tracts have further worsened these disparities,” said the authors.

How caste operates as a barrier to cancer care

The researchers highlight that “cancer awareness is often minimal” across the region. In rural north India, their review found that “only 20·6 percent of participants in a study knew that breast cancer was the most common type in the country, and over half were unaware of key warning signs that should prompt medical attention.”

Amongst marginalised communities, awareness is even lower. In tribal regions of southern India, a study found that whilst “over 80 percent had heard of cervical cancer, only 2·3 percent knew it could be detected early, and none had ever been screened.”

The study emphasises how “geographical isolation can also compound these barriers, particularly where health care facilities are sparse,” said the authors. Researchers found that rural Dalit women “face highest screening barriers,” illustrating how “factors such as caste, education, and rural residency influence cancer screening access in India.”

The broader pattern across South Asia shows that “urban centres concentrate cancer hospitals and specialists, while rural patients often travel hundreds of kilometres for diagnosis or treatment.” The researchers note that whilst “cities report higher cancer incidence due to better detection, rural areas bear higher mortality because patients arrive late or abandon care altogether.”

When caste compounds other identities

The research stressed that “caste, ethnicity, gender, and other marginalised identities intersect in complex ways, multiplying barriers to healthcare access across SAARC countries,” said the authors.

For Dalit women specifically, “these compounded identities not only affect access to health care but also exacerbate suboptimal outcomes due to neglect and discrimination within the system,” the researchers noted. The study stresses that interventions must recognise “how overlapping identities (caste, gender, and sexuality) create unique barriers.”

The study provides concrete evidence: “74·4 percent of Dalit women in India reported difficulties in accessing health care, and only 54·6 percent received professional antenatal care, compared with 70·3 percent of upper caste women.” Additionally, researchers note that “cancer stigma and gender roles limit timely care, especially for Dalit and rural women,” said the authors.

Religious identity adds complexity to caste-based discrimination. The analysis points out that “Dalit Christians and Muslims in India, while facing caste-based marginalisation, are excluded from government affirmative action programmes designed to uplift the scheduled castes.”

The researchers emphasise that “these intersecting factors of caste, religion, and socioeconomic status create a widening gap in health-care outcomes for patients with cancer from marginalised communities,” said the authors.

The study makes clear that “social stigma, cultural and religious beliefs, and financial toxicity often lead to avoidance of health-care facilities, further perpetuating inequitable access,” said the authors. These barriers operate simultaneously, creating what researchers describe as “compounded layers of oppression that drive inequitable health outcomes.”

Source: The South First