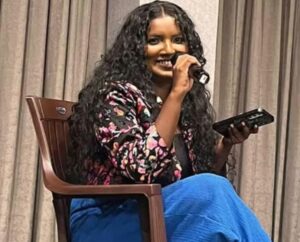

On April 23, Aleena, an acclaimed young poet from Kerala, read her poems in English and Malayalam at Atta Galata in Bengaluru. The event, organised by Moonbird Creative and attended by more than 100 people, also witnessed lively discussions. Aleena, a rising star on Instagram, a platform she uses to share poetry and create anti-caste awareness also shared her lived experiences within the Dalit Christian community and the politics surrounding their survival and resistance.

On April 23, Aleena, an acclaimed young poet from Kerala, read her poems in English and Malayalam at Atta Galata in Bengaluru. The event, organised by Moonbird Creative and attended by more than 100 people, also witnessed lively discussions. Aleena, a rising star on Instagram, a platform she uses to share poetry and create anti-caste awareness also shared her lived experiences within the Dalit Christian community and the politics surrounding their survival and resistance.

Aleena is the winner of the Kerala State Sahitya Akademi Kanakashree Award in 2021 for her debut poetry collection Silk Route. She writes in Malayalam and English, bringing together personal and political narratives in her poetry.

Her work has sparked viral conversations around casteism, identity, and representation, or the lack thereof, in the mainstream. Speaking to TNM, Aleena discussed her foray into writing, the Dalit presence in Indian media and what she’s got lined up next.

Can you talk about your early work and what drew you to writing poetry?

Aleena: I was uite the writer kid from my school days itself. So, writing was something that was with me from the beginning. Even during schooldays, I enjoyed being the writer kid. In schools, you get special attention from teachers if you are artistically inclined. Writing was the thing I latched onto.At first, I actually wanted to write fiction, but then I understood that it’s too hard for me, personally. Poetry comes a little more easily to me. It’s a more minute thing, while fiction is a bit larger. If you zoom into one thing, you get poetry, if you take a wider angle, you get fiction. So for uite a few years, I’ve been feeling like zooming in, that’s why I’m writing poetry.

How do you see the representation of Dalit voices in contemporary literature and popular culture?

Aleena: I think writing is the first artistic thing that Dalits did in modern or post-colonial India. I feel writing was and is a bit more accessible to Dalits than other forms of art, like making films or doing fine arts. You just have to learn how to write and put down your thoughts, maybe send them out to editors, publishers. Sometimes they accept it and sometimes they don’t. Then you look for other options for publishing it.

But I think writing is where most of our people are. Like, in Malayalam, we have a lot of poets from the community. But there are fiction writers only in limited numbers. What we have more of are autobiographies and memoirs because the [Dalit] life itself is very much absent in popular culture, let alone their art. We rarely see our lives in popular culture. It’s still exoticised, seen as other.

When someone is picking up a book by a Dalit artist or Dalit writer, they are looking for specific things that we do not get to see in Savarna literature. So, of course, we have to be represented more in terms of genres, like science fiction, fantasy, horror, and mythology. But, other than that, we have to get more into popular culture, like films, for example.

What I have also felt is that writing is a one-person job, so I can do it alone. But for films and other artworks, we have to have a network. This network is lacking so much in this community.

I think (Dalit) writing is there, but it’s still considered as something not marketable, or not widely read. It stays in some circles only. So that’s a problem we are facing because our society as a whole, is not uite ready to wholeheartedly accept our literature yet. I even face a lot of backlash for my poetry on Instagram. That’s because people are still not there mentally. And people can’t even ignore it, like, “let her say something, I’ll move on with my life.” No. They have to attack and say something. So it’s a bit messy. It affects our mental health, our work uality. A lot of time gets wasted.

Human rights of Dalits are being violated every day, there is news of communal violence all the time.

Is that what might be stopping artists from marginalised backgrounds from pursuing their art?

Aleena: I don’t feel like we uite think “how this piece is gonna be received” when we are making it. We do it because it involves a lot of pleasure when we are creating something. So nothing matters at that moment. But on putting it out there, they may begin to worry [about the response]. I started this page last year, and at first, I had like, 300 followers, only my friends and their friends. Then I wasn’t worried about anything because who’s gonna see it? I thought it would stay in our circles only, so people who don’t understand it or people who don’t uite agree with it won’t come and attack me. That’s what I thought.

But it just went a little out of hand. This visibility is also a curse for a person from a marginalised community. Social media gives us the visibility that traditional media is refusing to give us, but it also exposes us to a lot of violence.

What prompted you to start posting content on the Internet?

Aleena: It’s because I wanted to publish in English, but then I was totally lost there. I didn’t know how to do it because in the literature scene, everything happens through networks.

In Malayalam, we have a lot of poets from the community. So even though they lack the kind of economical privilege or the power to make decisions, they have cultural capital. If they are saying, “oh, this poet is good,” then we are automatically seen as good. So, the growth of Dalit literature in Malayalam has actually helped a lot of young poets like me to actually have it easier in the scene.

Otherwise, on top of creating good literature, you have to keep marketing yourself everyday. We all feel bad that we have to keep on doing this because we want to be discovered one day. We don’t want to be seen as a try-hard or something. It’s cringy, it’s embarrassing to do that (laughs). We feel like we are losing our dignity by doing that.

Because as artists, we are taught that marketing is bad. That art should speak for itself. So we are not perceiving marketing as ‘me as an artist taking space, where I’m denied space’. We don’t think like that. We feel embarrassed when we are doing it.

So then I thought, maybe I’ll start an Instagram page and then start putting my poems out there. Maybe someone will be able to connect to this. That’s the only aim I had in my mind.

How has the feedback been for your online content so far?

Aleena: I get a lot of love, a lot of support from people as well. At first, there were only hate comments. Because one person made a hate comment, Instagram thought “bigots are enjoying this, let me push it to more casteist people.” But then among this hatred, somehow I found people who actually enjoy my work, which is a blessing. Without that, I couldn’t have continued doing this.

Do you have any more works coming out soon?

Aleena: I wrote almost a hundred poems in English that I want to compile in a book. And I still haven’t finished editing it. And editing is, like, the most brainrot job.

I think it actually kills your ego. You are looking at a piece you wrote six months ago, through the eyes of a critic, and you feel so bad. Like, “Shit, What is this? You call this a poem?” (laughs)

And on other days, when we see the same poem, it’s like, “Wow! Who wrote it? Me!” So this is like waves. Waves of being a poet- confidence and insecurity.

What do you hope an audience can take away from such poetry gatherings?

Aleena: Maybe a more nuanced perspective. Because I’m a woman, I’m Dalit, I’m a Christian, and I’m a first generation graduate. And at the same time, I feel like I don’t represent the larger context of my community because I got education, and I speak English. So I’m maybe, like, 10% of the community. And it is for the same reason that I feel compelled to talk about this. Because, if I’m not doing it, it would affect my conscience.

The stories and everything we have heard, if nobody is recording them, who’s gonna preserve it? I’m sure we have lost a lot of stories.

Would you like to recommend any particular books or movies from the community?

Aleena: Movies I don’t uite know about. Some movies, especially in Tamil, have a lot of violence. A Dalit person’s life is not violence. It’s one aspect of it. Some people like to highlight the violent part or the atrocity part, but, that’s not uite all of it.

We have a lot of books like the works of Suraj Yengde, Yashika Dutt and Sumeet Samos. There are poets like Jacinta (Kerketta) and Sripath.

Source: News Minutes